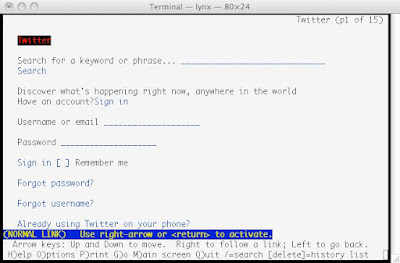

The following video shows my attempts to use the mobile versions of Facebook and Twitter with Lynx, the textual browser. Facebook fails, while Twitter successfully logs me in and lets me publish a tweet. I hope you find it useful.

Showing posts with label accessibility. Show all posts

Accessibility and CSS

One of the main goals of CSS, beside separating structure from presentation, is to enhance the accessibility of a web page. This presentation shows and outlines the key areas where CSS comes to rescue when dealing with page accessibility. A further reading is surely Accessibility features of CSS by the W3C.

Color contrast and web design

Can web design and accessibility live together? Can they coexist? Only under certain conditions. The first condition concerns the choice of the color palette. Color contrast, that is, the contrast between foreground and background color must be accessible. For accessible, I mean that it must follow and fulfill all the W3C requirements that are clearly expressed in the Contrast Analyser tool. This is a no-no condition. For example, the following image shows a wrong color contrast.

In this case, white and orange cannot be used together. Period. But if you don't want to throw away your own design, there's a simple solution: provide an alternate design to be delivered to users with special accessibility needs (such as blind-color users or users with some other color impairment or even low-vision users). This solution is up to you: if your site must be accessible for whatever reason (e.g. legal, like Section 508), then you have to consider this solution. Otherwise, it's only a matter of personal choice.

Accessibility and JavaScript drag and drop

The point of all JavaScript coding is to enrich the user experience without burdening the user with a cognitive and physical overload. The problem with JavaScript drag and drop is that it forces the user to perform additional gestures to get the desired result (moving an item to the shopping cart, moving it again to the trash and so on). For users with physical disabilities this can actually turn out to be very stressing and frustrating. An user who has slow gestures due to his/her age won't be probably able to perform simple tasks such as pointing and clicking the mouse on an item and then moving it around the screen.

Further, drag and drop doesn't exist in JavaScript per se. Internet Explorer supports certain events related to this practice, such as dragstart, but there are no correlatives either in other browsers or in the specifications. Simply put, what you see is the result of a continuous mapping and tracking of the mouse coordinates on the screen, combined with other mouse events, such as mouseleave.

For that reason, drag and drop is not supposed to work in all possible circumstances. For example, Blogger uses this technique to rearrange blog templates. In certain cases and browsers, it doesn't work as it should. And the final effect on a Blogger user is only one: frustration. I know that drag and drop is certainly a nice touch on a site, but you should always bear in mind how this feature will be perceived by your users and, to a less extent, by browsers.

jQuery, Ajax and accessibility

Most developers tend to overuse Ajax for the sake of the large amount of features and enhancements that can be added to a web application through this widespread technology. However, this abuse poses some major accessibility problems that I'd like to outline here by taking the jQuery library as an example of Ajax-enabled framework.

The problem of updated content

With jQuery is really easy to update the content of a given HTML element to reflect a change in the Ajax response. For example, we can use the load() method to insert some HTML code on a target element. The problem with this approach is that the overwhelming majority of screen readers won't be able to properly read the new updated content. A screen reader usually comes with an internal feature called virtual memory, that is, a buffer-based portion of its memory where it can load the entire content of a document and store it for later use.

Unfortunately, all screen readers have this option disabled by default, so if a user doesn't activate it, the entire document won't be kept in memory. From an Ajax perspective, this means that when you update an element with an Ajax response, the screen reader won't even notice it and it will continue to read the normal content. A simple solution in this case would be the WAI-ARIA roles. The problem with this solution is that is still under development and it will take some time to get a massive adoption by browsers and screen readers.

Further, a screen reader could even get confused and start reading the whole document again. Imagine what might happen if your page contains a lot of content.

The problem of links

Link targets should not be empty. Most developers use links with an empty href attribute and this is a bad practice. If a user-agent doesn't support Ajax, an empty link make it reload the entire document. Further, also dynamic links should be avoided. For dynamic links I mean those links created via JavaScript. Remember that screen readers can handle properly only certain DOM events, such as load. If your links are generated through a call-to-action that is fired with an event that screen readers don't support well (or don't support at all), then your links won't be generated.

You can use anchors (hashes) to make your links point to an effective portion of your page. This will avoid the problem of empty links and offer some kind of reference for browsers or agents that don't support Ajax.

The problem of widgets

Progress bars, spinners and the like are all nice Ajax widgets. However, since they're all made for a presentational purpose, they should not be inserted in the markup. Further, they should not convey any semantic information that could be possibly relevant for the correct use of a document. In other words, you should not rely on them, because it's always a good practice to provide alternate ways of informing a user.

The problems of events

Screen readers don't support DOM events very well. There's no universal rule to use with screen readers, because there are many differences among them. The only thing that we know for sure is that they support the load event. For other events, there's no rule of thumb for dealing with them, so you're warned.

The Legend of the Typical Screen Reader User

Check out this SlideShare Presentation:

Accessibility support to HTML5

Today Roberto Castaldo posted a message on the Webaccessibile Italian mailing list sharing his translation of an invaluable resource of Steven Faulkner about HTML5 and accessibility.

More precisely, Steven's site contains a comparative table that shows the current accessibility support to HTML5 elements in the most used web browsers. If you take a look at the table, you will probably notice that almost all HTML5 elements listed there are not supported by browsers from an accessibility point of view. Although these elements are actually implemented, there are no additional accessibility features attached to them. For example, the video and audio elements lack of support to certain keyboard shortcuts in all browsers.

If we want to learn a lesson from this, we should stick to traditional HTML 4 and XHTML elements as long as browsers extend their support to the accessibility features required to make HTML5 elements fully accessible even to assistive technologies. Bear in mind, however, that HTML 4 elements are perfectly valid HTML5 elements, so there are no problems with this approach.

CAPTCHA images considered harmful

Just a couple of minutes ago I've updated my profile on Amazon by providing an alternate email address. The main problem encountered during this procedure was recognizing the correct character sequence in the CAPTCHA image. I had to try several times before typing the correct sequence. So my point is: if a sighted user has encountered so much problems with CAPTCHA images, what will happen to a visually impaired person who tries to fill in the form?

I'm not talking about blind users who can still get an alternate version of the CAPTCHA. I'm simply talking about persons who do not have a perfect sight. Honestly, I was frustrated by this. I kept typing my password, my new email and then.. nothing! Or, even worse, an error message claiming that the characters inserted weren't correct. Now you may ask if there's a feasible alternative to images. The answer is... yes! Simply put, use a textual alternative, for example by asking a simple question that only a human reader can understand (e.g. "What is the capital of the United States?").

What's more, you can actually get rid of a lot of server-side procedures used to creating, changing and inserting the CAPTCHA image. The only problem with this approach lies in the correct choice of some good questions. Anyway, surely we'll prevent our users from being frustrated when they try to decipher the CAPTCHA image and get some error.

Cross Device Accessibility

Check out this SlideShare Presentation from Opera Software:

Dialup is not dead

Sometimes I check my Google Analytics stats to find out something about my visitors. Today I found out that some of my visitors use a dialup connection. More precisely, 74 visitors during the last month. I must apologize with these visitors if they found my site really heavy to load. The fact is that I'm lazy and easily distracted. I don't check my stats on a regular base, so I missed some important details. People who use a fast connection often forget how much a dialup connection is slow. I mean, really slow. Dialup connections are the last signs and relics of the World Wide Wait model of the '90s. Anyway, if accessibility and usability really matter, we can't overlook this datum. We should provide a way to access our site contents in a reasonable time span. If I think that my 74 visitors had to wait almost a minute to load my blog, there's only one thing that comes into my mind: I am a stupid!

Sometimes I check my Google Analytics stats to find out something about my visitors. Today I found out that some of my visitors use a dialup connection. More precisely, 74 visitors during the last month. I must apologize with these visitors if they found my site really heavy to load. The fact is that I'm lazy and easily distracted. I don't check my stats on a regular base, so I missed some important details. People who use a fast connection often forget how much a dialup connection is slow. I mean, really slow. Dialup connections are the last signs and relics of the World Wide Wait model of the '90s. Anyway, if accessibility and usability really matter, we can't overlook this datum. We should provide a way to access our site contents in a reasonable time span. If I think that my 74 visitors had to wait almost a minute to load my blog, there's only one thing that comes into my mind: I am a stupid!

Yes, stupid. Because I've burdened my blog with a lot of extra widgets that add a really little meaning to the overall context. Users, contents, context: in a word, usability. As developers, we must take a decision: developing a web site that takes into account all the needs of dialup users or, on the contrary, an oversized web site with a lot of widgets and micro applications. Of course there's no need to be drastic. If those widgets are really important to the site, we should provide a low-content version of our pages, for example removing all unnecessary widgets and graphics (and scripts too). By doing so, dialup users won't have to wait a month until a page finishes loading. And this is all good reputation that we actually get and if we plan a site accordingly, we deserve it.

Making Rich Internet Applications Accessible Through jQuery

Check out this SlideShare Presentation:

Facebook: the client-side code is a mess

No kidding. If you take a look at the source code of any Facebook page (for example, your home page), you will see something quite shocking: the 80%-90% of the page is made up by JavaScript code! That's why Facebook doesn't work with assistive technologies: there's very few actual content to parse and render in such pages. Facebook seems to embrace the what-you-see-is-what-you-get philosophy or, as they put it, we're not cool enough to support your browser (said to a Lynx user).

Fine. So they don't care if many users can't access their web application. But there's another thing that needs to be emphasized: by relying so heavily on JavaScript and Ajax, Facebook delivers a consistent parsing and rendering load to web browsers. Sure, JavaScript engines evolve, but what about backward compatibility? There should be a certain balance between effective content and JavaScript-generated content. Facebook is completely unbalanced. And yes, this is a mess. No kidding.

No kidding. If you take a look at the source code of any Facebook page (for example, your home page), you will see something quite shocking: the 80%-90% of the page is made up by JavaScript code! That's why Facebook doesn't work with assistive technologies: there's very few actual content to parse and render in such pages. Facebook seems to embrace the what-you-see-is-what-you-get philosophy or, as they put it, we're not cool enough to support your browser (said to a Lynx user).

Fine. So they don't care if many users can't access their web application. But there's another thing that needs to be emphasized: by relying so heavily on JavaScript and Ajax, Facebook delivers a consistent parsing and rendering load to web browsers. Sure, JavaScript engines evolve, but what about backward compatibility? There should be a certain balance between effective content and JavaScript-generated content. Facebook is completely unbalanced. And yes, this is a mess. No kidding.

Accessible Javascript using Frameworks

Check out this SlideShare Presentation:

HTML5 & Accessibility

Check out this SlideShare Presentation:

CSS experiments and accessibility

Steve Dennis published a stunning experiment using some advanced features of CSS3, such as animations and borders. The main problem with this kind of experiments (I've been there myself) is notifying to assistive technologies (which don't support CSS at all) that all the markup inserted in a given element has only a visual purpose, that is, that they don't need to read it and they can actually skip it.

Since most of the CSS experiments I've seen so far use some kind of wrapper to show their contents, it would be useful if web developers use an hidden element to inform assistive technologies users that what they're reading is actually a visual demo, like so:

<div id="experiment"> <div id="experiment-notice"> This is a visual experiment made with CSS3 that shows a whale falling from the sky into the ocean. Thanks to CSS3, the whole demo is animated. </div> <!-- experiment content here --> </div>

You can hide this notice very easily:

#experiment-notice {

position: absolute;

top: -1000em;

width: 1px;

height: 1px;

overflow: hidden;

}

By doing so, users who surf the web with assistive technologies can actually get a full experience of your contents. I'd like to thank Michele Diodati who first pointed out this issue viewing my experiments.

Twitter doesn't support assistive technologies

In an earlier post I showed how Facebook doesn't actually support assistive technologies such as Lynx. This time I've run the same tests on Twitter and the results are almost the same. The only exception is that when you load the home page of this web application you don't get any message claiming that your browser is not supported, as shown below:

Everything seems ok. But if you try to log in entering invalid data, you get nothing:

Since most probably error messages are generated by JavaScript, Lynx can't show them. But even if you enter correct data, you can't access to your account because you get an error due to SSL:

Finally, since I was already pretty frustrated, I decided to use the search function of Twitter. Guess what? Nothing again!

What we've got so far? All web applications tested, namely Facebook and Twitter, are virtually inaccessible to assistive technologies. That's too bad. We've only to wait. And hope.

Ideas 5 - Roger Hudson - Understanding WCAG 2.0

Check out this SlideShare Presentation:

Accessibility and the importance of user testing

Check out this SlideShare Presentation:

Back To Basics - Web standards and accessibility

Check out this SlideShare Presentation:

CSS, JavaScript and accessibility workshops 2010

Great presentation by Russ Weakley.